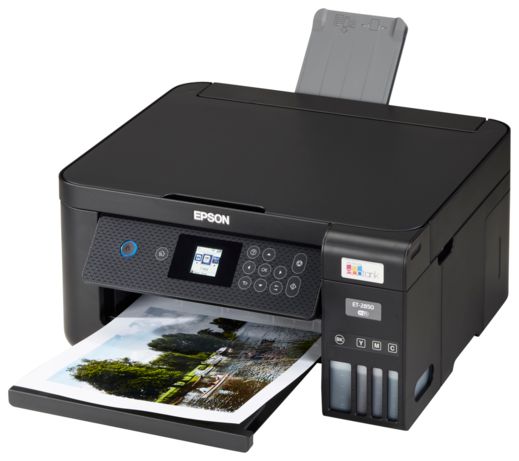

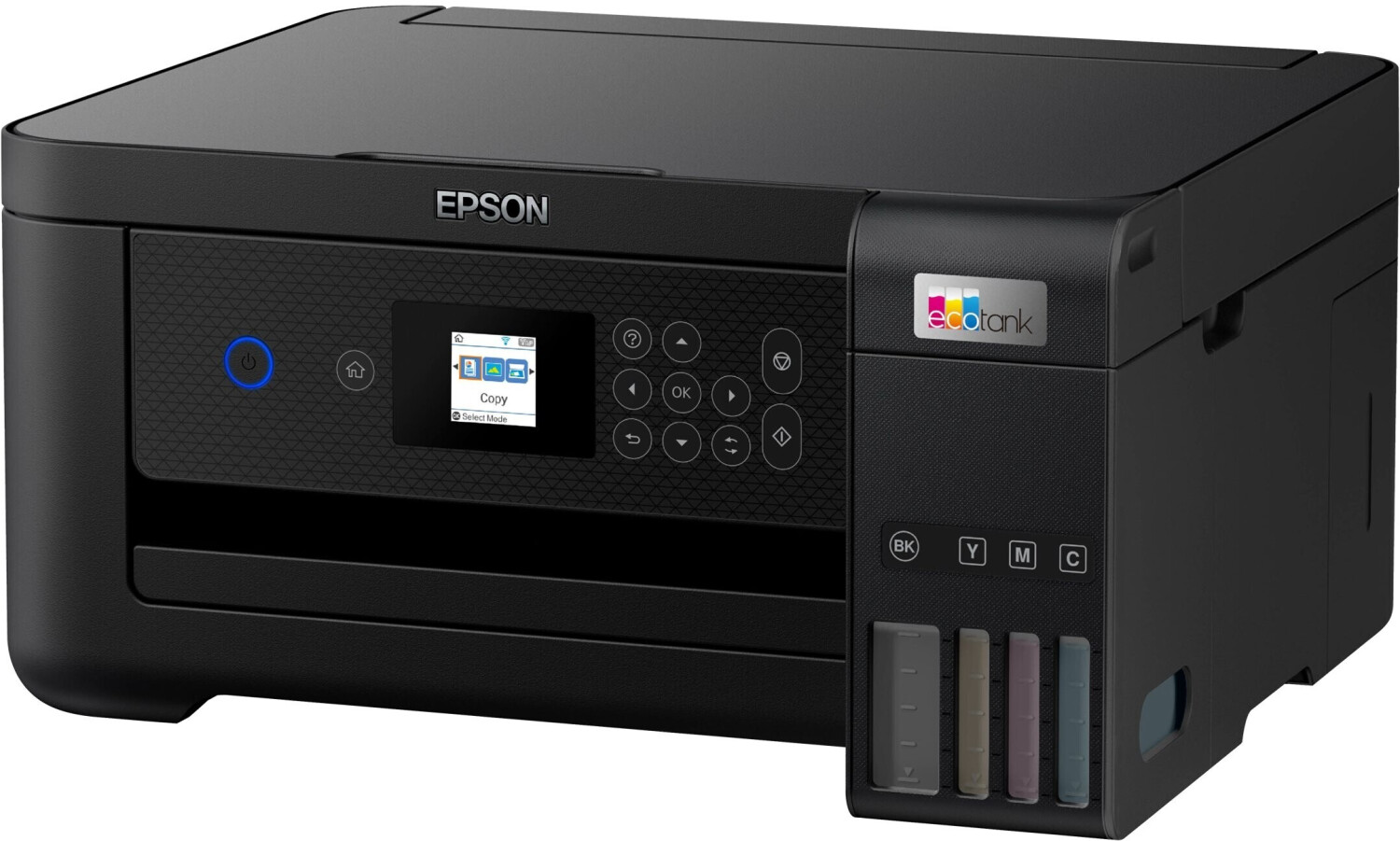

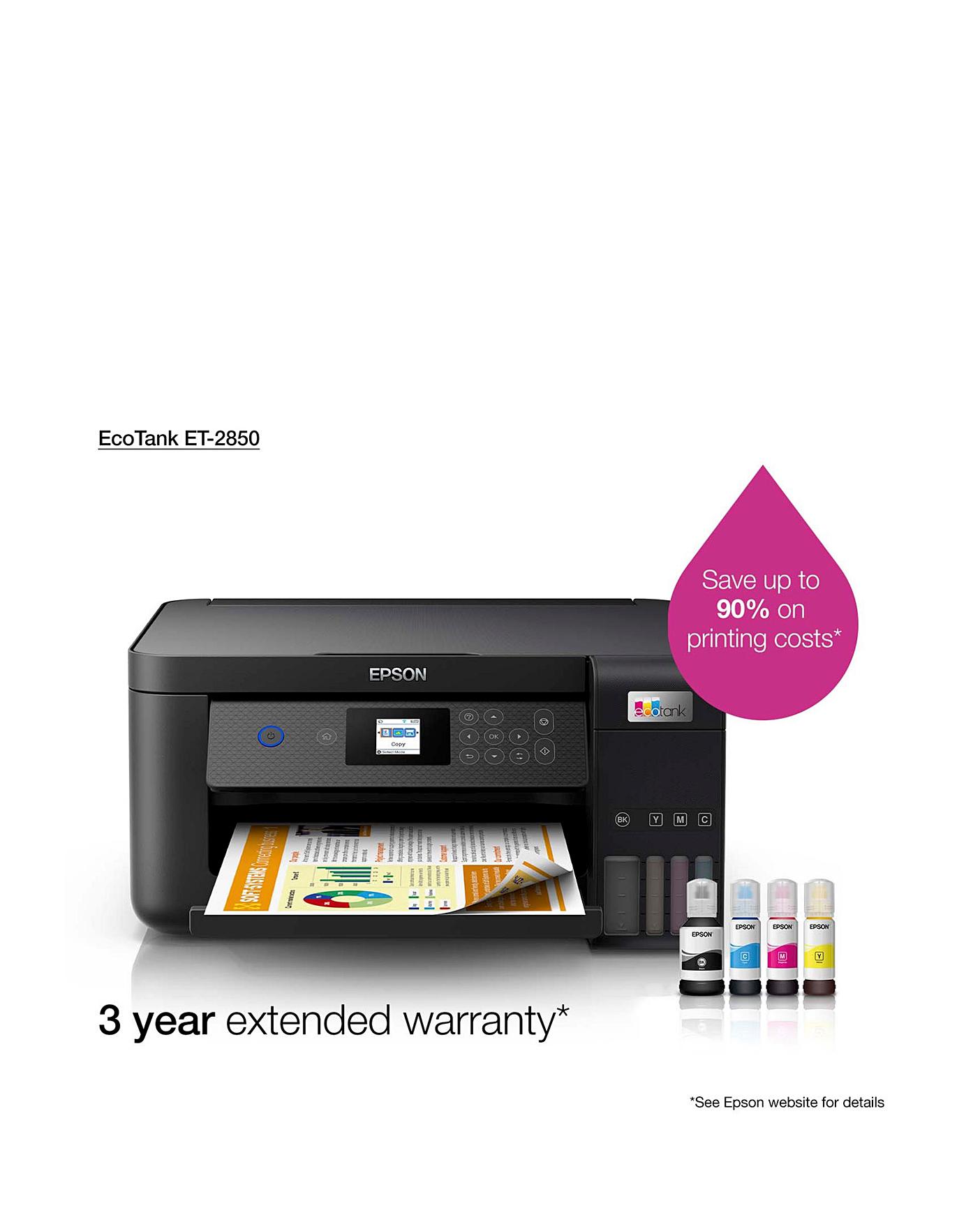

Epson EcoTank ET-2850 Three-In-One Wi-Fi Printer with High Capacity Integrated Ink Tank System, Black

Epson EcoTank ET-2850 Three-In-One Wi-Fi Printer with High Capacity Integrated Ink Tank System, Black

EcoTank ET-2850 Wireless Color All-in-One Cartridge-Free Supertank Printer with Scan, Copy and Auto 2-sided Printing | Products | Epson US

kwmobile Dust Cover Compatible with Epson EcoTank ET-2850 / EcoTank ET-2856 - Printer Case - Fabric Protector Cover - Dark Grey: Amazon.co.uk: Computers & Accessories

Epson EcoTank ET-2850 A4 Multifunction Wi-Fi Ink Tank Printer, With Up To 3 Years Of Ink Included : Amazon.co.uk: Computers & Accessories

Epson EcoTank ET-2850 All In One Supertank Printer at Rs 17000/piece | Epson Multifunction printer in Siddapur | ID: 2852754160388